Part of Being Human

Surveys show that most people believe they are less biased than average. Obviously, that belief cannot be true unless we all live in Lake Wobegon where “all the children are above average.”

In fact, we are all biased—it is simply the reality of the human condition. Studies show that prejudices are hard-wired in our brains. There is a region of our brain called the amygdala that reacts when we encounter people we judge as different or unfamiliar (Fiske, 2007). The amygdala is the vigilance center of the brain that helps to keep us aware of things (or people) we find potentially threatening. For example, the amygdala is activated when people are shown faces of a different race. If we don’t personally know someone from another race, our brain reacts as if this person may be a threat to us.

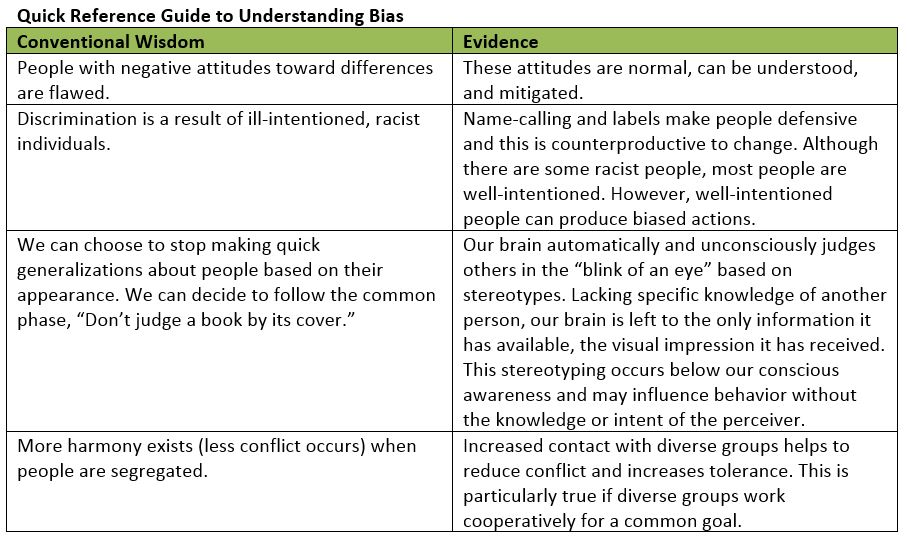

In addition to perceiving the unknown as a threat, our brains try to compensate by filling in details based on the only available information our eyes can quickly gather, which is often based on stereotypes associated with that person’s group. Although this phenomenon is most associated with race, it happens all the time: We make judgments about strangers based on their hair, weight, clothing, piercings, tattoos, etc. These judgments happen below our conscious awareness (Payne, 2001). Our brains are always looking for various cues that help to make instantaneous assessments about others.

A great deal of prejudice is both automatic and unconscious. People favor their own groups over others, and this preference occurs automatically. Neuroscience has shown that we can identify a person’s race, gender, and age in milliseconds. Social psychologists explain that there is an “implicit system” in our brains that is designed to be reactive instead of reasoned, and it produces quick generalizations (Gladwell, 2005). These mental shortcuts are often necessary for us to appropriately react quickly without taking the time to think about the necessary reaction. It is what author Malcolm Gladwell calls “thinking without thinking,” or rapid cognition, in his book Blink.

Although this ability is important to keep us safe, it can also misguide us. Researcher Susan T. Fiske has conducted experiments in which she showed test subjects photographs of homeless people. People reacted strongly to the photographs with instantaneous feelings of disgust and avoidance. It is interesting to note that even absent a person’s presence, a photo can evoke such a strong negative reaction (Fiske, 2008).

Why It Matters

Why does it matter that our brains privately, instantaneously and unconsciously think negative thoughts about those who are different than us? Several lines of research have discovered a clear connection between our snap judgments and our actions. For example, our brains will tend to link an unfamiliar black person to criminal behavior. Absent other available data, we link “blackness” with crime—quickly and automatically—regardless of whether there’s a rational basis for that link.

Interestingly, this black-crime link also occurs in the brains of many black subjects. They, too, often link blackness (of those they do not know) with crime. Surveys conducted with both white and black women walking down the street determined that women of both races were automatically more afraid if a black stranger was walking behind them than if a white stranger was walking behind them. Similarly, when people are shown portraits of black faces (primed with images of blackness), they are much faster at identifying crime objects on a computer screen than when first primed with white faces (Payne, 2001).

This black-crime link has major implications for interactions between law enforcement officers and black citizens. It is critical that we understand the tendency to link blackness with criminal behavior, and we must work to ensure that we are acting in a fair and impartial manner (Fridell, 2001). Stanford psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt discovered that these rapid perceptions can also have very negative impacts on the fairness of sentences given by judges. For example, when analyzing the sentences given to convicted criminals, it was found that black men were more than twice as likely to be sentenced to death if they had more “stereotypically black” facial features (Eberhardt, 2004).

Race tends to be a flashpoint in some police use of force cases, but implicit bias extends well beyond race. Gladwell relates a story about gender bias: In 1980, a German musician named Abbie Conant received a letter in the mail inviting her to audition for the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra. The letter was addressed to Herr (“Mr.”) Conant. Conant dismissed the mistake as a typographical error and attended the audition.

The auditioning musicians were required to play anonymously, behind a screen, because one of the judges had a relative seeking a job and wanted to ensure that the process was fair. Conant played the trombone and did so with great power and skill. Immediately following her performance, she was offered a job—but the judges still had no idea she was a woman. When they discovered her gender, they were shocked; at the time, women musicians were limited to “feminine” instruments such as oboe or violin. The judges wanted to withdraw the job offer, but they needed a reason. They forced Conant to audition two more times, but she passed both auditions. They then made her take tests to determine her lung capacity—she scored high on all tests. Ultimately, she was saved by the screen and by the unbiased ear. This is a classic example of how our eyes misguide us.

So, aren’t people still to blame for their biased thoughts and actions? After all, not all people act upon their biases, even if their first impulses are biased ones. In short, blame is not useful. Blame tends to make people defensive and curtails learning. Although there certainly are mean-spirited and racist people, most people are not ill-intentioned racists. In fact, most people are well-meaning. However, because these snap judgments occur below our conscious awareness, even well-meaning people can produce biased actions.

What Can We Do?

What can we do to mitigate implicit bias? Recent research has demonstrated the value of something called the “contact theory.” This theory states that increased contact between members of different groups can reduce conflicts and prejudices.

For example, a study done by Thomas Pettigrew (University of California-Santa Cruz) and Linda Tropp (University of Massachusetts-Amherst) showed that school integration reduces prejudice among students from different groups. This is accomplished not by simply placing people together, but instead by creating situations in which they must cooperate to succeed (Pettigrew, 1997). As contact between minority groups increases, so do positive attitudes between those groups. In other words, people tend to harbor more negative attitudes toward those they are less familiar with (or have less contact with) and tend to have positive attitudes toward those they interact with more often.

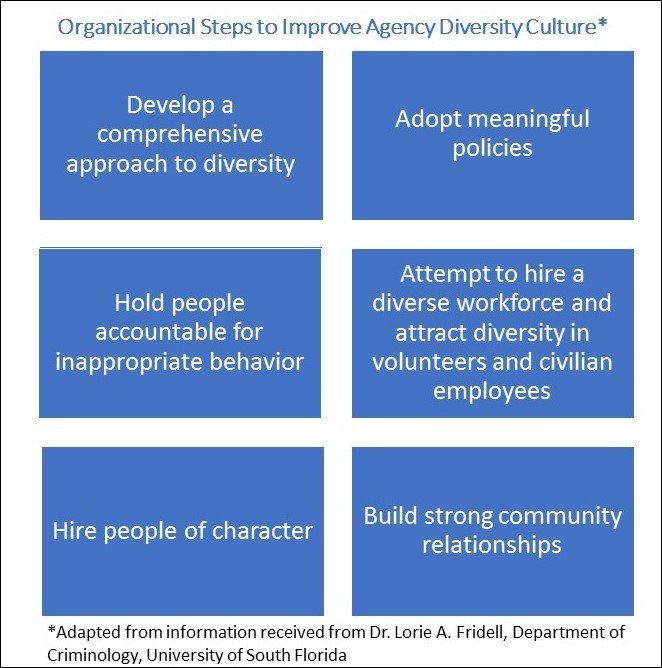

Applied to law enforcement, this theory provides additional motivation to strengthen our community policing initiatives. It also has implications in the law enforcement workforce: If we diversify the workplace, we can reduce prejudice and discrimination.

It’s true that implicit bias is based on our biology. But prejudices are not inevitable, and understanding the biology of our brains does not in any way reduce individual responsibility for our actions. Understanding the science behind bias can help us to pause, reevaluate potential unfair conclusions, and mitigate harm. Even though we have an automatic response to what we see (on the surface) in others, our brains are amazingly malleable and can rein-in unwanted prejudice in favor of thoughtful, fair choices. Put simply: Knowledge of how we are wired can help reduce prejudice.

References

- Eberhardt JL, Goff PA, Purdie VJ, Davies PG. Seeing black: Race, crime, and visual processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2004;87:876–993.

- Fiske ST. Look twice. Greater Good Magazine. 2008;5(1):14–17.

- Fridell L, Lunney R, Diamond D, Kubu B. Racially Biased Policing: A Principled Response. The Police Executive Research Forum: Washington, DC, 2001.

- Gladwell M. Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. Little, Brown and Company: New York, NY, 2005.

- Payne BK. Prejudice and perception: The role of automatic and controlled processes in misperceiving a weapon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:1–12.

- Pettigrew TF. Generalized intergroup contact effects on prejudice. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin. 1997;12:173–185.