Editor’s note: This article is part of a series. Click here for the previous article.

Gordon Graham here and hello again. Thanks for taking the time to read these ramblings regarding the importance of “real risk management” in public safety operations. While each of these articles is meant to work as a stand-alone piece, I also encourage you to go back to the beginning of this series if you haven’t been following along.

We’ve been moving through the 10 Families of Risk that everyone in public safety faces—and more importantly, what can be done to address these risks. We are now in Family Five – Operational Risks, or all the things that can go wrong in our day-to-day operations. Managing operational risks is about ensuring things go right rather than wrong, thus avoiding the nasty consequences that occur when things do go wrong.

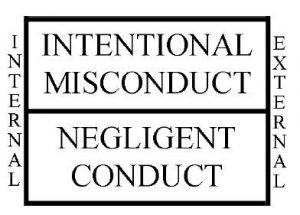

A few articles back, I introduced a chart that helps us organize how we think about operational risks:

We have addressed the problems caused by intentional misconduct (both external and internal) and those caused by external negligence. In this article, I’ll focus on internal negligent conduct in public safety. Simply stated, this is where our own good people make honest mistakes.

It is difficult to prevent intentional misconduct, whether it comes from the inside or outside, and it is difficult to address external negligence. But internal negligence can be addressed quite easily. This is why I am “high” on the discipline of risk management. There is so much we can do to prevent internal error. If we can identify where our people make mistakes in any given aspect of public safety work, then we can put together control measures to address these issues proactively.

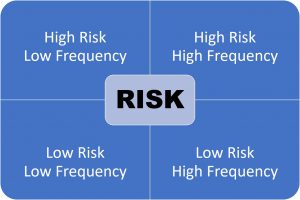

Here is another chart for your consideration:

This chart is known as the risk/frequency analysis. Everything that gets done in every job in your operations can be put into one of these four boxes.

If you have been to any of my live programs over the last 40 years, you have seen this chart before. But please do not give me credit for inventing it—I did not! I modified it just a bit in 1980 as I fine-tuned my work back then (I will explain this important modification in a later article).

Why did I have to wait for a specialized course in grad school to learn something everyone should know by the time they graduate high school?

This chart was introduced to me in graduate school in 1975, and even then I had a question: Why, why, why did I only learn about this now? Why did I not learn this in high school? Why did I not learn this at the California Highway Patrol Academy? Why did I have to wait for a specialized course in grad school to learn something everyone should know by the time they graduate high school?

And my question to you as a leader in public safety is this: When are your people going to be introduced to this chart? When are they going to learn that most of the trouble they get involved in starts with an employee making a mistake? When are they going to learn where mistakes happen, and what can be done to lessen the likelihood of making a mistake that may well end up in tragedy?

And here I go on another digression. I have been cautioned by the editor of these articles not to say anything that dates the writing because some cop or firefighter or correctional officer or risk manager in 2099 could be reading this—and we want the lesson to be timeless.

But, not that long ago I got a call from a friend who has done so much for so many over his five decades in law enforcement. He now runs a police academy here in Southern California and he asked that I address some police trainees who are in their final week in the academy. Take a wild guess what I topic I picked to address these brand-new cops!

If you understand the risk/frequency analysis chart, you can predict where most mistakes will occur. And please remember that mistakes are the cause of too many public safety tragedies.

And that’s what we’ve delve into next time. Thanks for reading!