Editor’s note: This article is part of a series. Click here for the previous article.

Gordon Graham here! Thanks so much for your continued great work in trying to improve the quality of public safety services in the United States. I am so grateful that you read these brief articles regarding the value of implementing risk management strategies into your operations.

It is time for a brief update on where we are in this series. I believe all the risks you face in public safety can be put into 10 families. Here is a graphic many of you have seen before, but for those of you who are new to these writings it will show you where we have been on this trek—and where we’re headed.

We have covered the first four families, so let’s move on to family five, operational risk management—or more simply stated, how to manage the risk of a specific task, incident or event in which your people get involved.

Here is some good news for you: The vast majority of things your people do—your dispatchers, your patrol people, your line firefighters, your correctional officers, and everyone else—they are doing right.

My concern is the specific consequences that occur when things don’t go right. These consequences include death, injury, personal and professional embarrassment, internal affairs investigations, lawsuits, negative impacts on criminal prosecutions and, yes, even the rare criminal filing against our own personnel.

If you ask your city attorney what causes these tragedies, you will probably get the “proximate” cause: the engineer ran the red light, the dispatcher hung up on the caller, the under cover operator was not in uniform and people did not recognize her as a cop, the front desk officer inappropriately released the report prior to it being redacted. Lawyers tend to focus on the event that immediately preceded the tragedy.

But if you ask a “real” risk manager the same question, they tend to go back in time—long before the proximate cause—and they look for the “problems lying in wait.” When you identify these problems, it generally gets down to two things: Someone did something bad on purpose, or someone made a mistake.

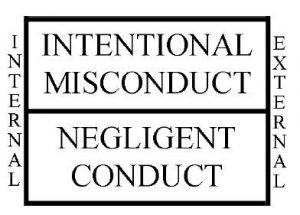

If you have been to my live programs over the years, you may remember this graphic:

Public safety personnel get in trouble for the above two things—intentional misconduct and negligent conduct. Now if you are really paying attention, you will note that I have excluded another way we get in trouble: acts of God and/or acts of Mother Nature. We have no control over those events (but our response to them is an identifiable risk and thus something we need to be concerned with), so let’s talk about what we do have some control over: human behavior.

Some of the behaviors that get us in trouble are generated externally (by people outside our agency), and some are generated internally (by our personnel). Let’s take these one at a time (over a period of several articles) so we can start to practice RPM—Recognize, Prioritize, Mobilize—to properly address these external and internal risks.

Let’s start with the top right portion of the above graphic: external intentional misconduct. More simply stated, these are behaviors by bad people who are not members of our organization. These behaviors include but are not limited to arson, assaults on our personnel, terrorism, cyberattacks and other behavior designed to harm public safety personnel and/or equipment or facilities.

I don’t want to rain on your parade, but in a free society (like the U.S.) it is very, very difficult to stop a bad person who is bent on behaving badly.

Not too long ago, I had the pleasure of presenting at Bolton Landing in the beautiful state of New York. Bolton Landing is a very impressive location on Lake George. As I headed back to Albany to catch a plane, it hit me that if some jerk (terrorist, arsonist or emotionally disturbed person) wanted to light an arson fire in this gorgeous setting, she/he could do it with great ease.

As I was on my morning walk today, I saw two police motorcycle officers on Pacific Coast Highway. Here is a scary thought for you: If some criminal or terrorist wanted to run over both these officers, she/he could do that with great ease. As I prepare this piece, I’m thinking about the two bike cops in the greater D.C. area who were run down in 2017. While not a terrorist event per se, the method used in this attack is becoming a favorite of terrorists.

Look at the recent terrorist murders in England, France, Germany and Belgium using trucks and other large vehicles. From a cost/benefit analysis, this is a cheap and very effective way to kill innocents (including cops and firefighters) and as such, you can bet this type of attack will be replicated many times around the world—and right here in the United States. In fact, this “momentum weapon” is a recommended terrorist technique, as evidenced by publications put out by terrorist groups.

With an eye on my word count, I’ll leave things there. In my next article I will explore external intentional misconduct in greater detail and give you some control measures. Thanks for reading!

TIMELY TAKEAWAY—On one of my trips to the U.K. I met a fellow who was with the Northern Ireland Police. We keep in touch; he is one of the great thinkers in our profession. Check out his concept paper on responding to “momentum weapons.” Hopefully you can use this information to better protect your personnel and your community.

TIMELY TAKEAWAY—On one of my trips to the U.K. I met a fellow who was with the Northern Ireland Police. We keep in touch; he is one of the great thinkers in our profession. Check out his concept paper on responding to “momentum weapons.” Hopefully you can use this information to better protect your personnel and your community.