Editor’s note: This article is part of a series. Click here for the previous article.

Gordon Graham here again and let me get you caught up with where we are in this effort to incorporate “real” risk management into everything that gets done in public safety operations.

I cannot say this often enough: Most of what your people are doing, they are doing right. The combination of good people performing high-frequency tasks is very powerful. They become experts at what they do, and they generally do it efficiently, safely and effectively.

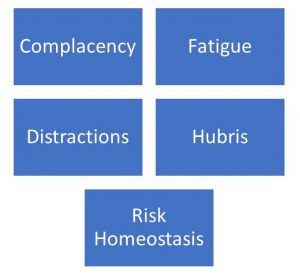

However, occasionally our personnel get in trouble on high-frequency events and when they do, it’s because of one of five “problems lying in wait”:

In past articles I gave you some thoughts on the dangers of complacency, fatigue and distractions. This time, I want to cover hubris.

Hubris. I just looked up the definition in Miriam-Webster and their interpretation of the word is “exaggerated pride or self-confidence.” I have another word for it—cockiness.

Please don’t get cocky. Regardless of occupation or profession, when people get cocky, it’s a ticket for tragedy. I love confident cops—but cocky cops (or pilots, or firefighters or public works people) are going to get in trouble.

O.J. understood the meaning of “capital punishment”—the more capital you got, the less punishment you get!

To illustrate this, let’s go back some 20-plus years to the O.J. Simpson trial. There are a lot of reasons the O.J. verdict was “not guilty.” You can look at how the district attorney moved the trial from West Los Angeles to downtown, or that the DA did not put his best prosecutors on the case, fearful they would use their fame to run against him in an election. Or you can blame it all on Mark Fuhrman. But as I analyze the result, the “H” word keeps popping up.

LAPD homicide cops are very, very, very good at what they do. They have a high arrest percentage and a high percentage of guilty pleas or verdicts. I was always impressed by their work when I was active in the LA area—and I remain so today.

In fact, I think they got so good at what they did in the 1980s (high arrest numbers and high conviction numbers) that they got a little cocky. They kept on winning and winning and winning!

But when I dug deeper, it became clear why LAPD had so many pleas and guilty verdicts in homicide cases: Most of the defendants were represented by public defenders. Now I don’t know the caseload of PDs in your jurisdiction, but in LA they are grossly overburdened with cases—there is, after all, lots of criminal stuff going on in the City of Angels—and they historically have been understaffed.

So the PDs were good at taking pleas (“Take the 25-year offer, because if it goes to trial it could end up in a death penalty”) and when they did take a case to trial, it was hardly the only case they had.

Now, LAPD had a policy on how to investigate murders. It was properly designed and it was up to date. It was very specific regarding the responsibilities of the “first-in” detective, the importance of securing the crime scene, how to talk to witnesses, how to collect evidence, how to book evidence, etc.

I was and am convinced these LAPD cops were not bad cops—but they were “cocky cops” and hubris ended up causing them grief.

But over a period of years (and I have heard this from many inside LAPD), their level of adherence to the policy decreased. They were still getting pleas and convictions because the PDs were so busy and overworked they did not get into the minutiae involved in the investigation. But there was a growing problem lying in wait.

And you know the rest of the story. When the detectives showed up on Gretna Green Way on June 12, 1994 (oddly enough, my dentist’s mother lived next door to the scene of the crime), they did not follow all the written rules regarding crime scenes and witness interviews and collection and preservation of evidence. And 16 months later, a jury found O.J. not guilty.

What was different about this case? O.J. did not have a public defender. O.J. understood the meaning of “capital punishment”—the more capital you got, the less punishment you get! He got a good lawyer—actually five good lawyers—and they took the LAPD detectives apart, not on corpus delecti, but rather on their failure to follow the guidelines set out in their policies on murder investigations. I was and am convinced these LAPD cops were not bad cops—but they were “cocky cops” and hubris ended up causing them grief.

There are countless other cases involving motor cops and public safety pilots and dispatchers and others in our high-risk business who get cocky (synonym: arrogant) and the result is an unfavorable outcome.

So there you have it—my take on the case that captivated the nation almost 26 years ago. Hard to believe it is still in the news.

That’s it for this writing. In my next piece I will wrap up this portion of my ramblings with some thoughts on risk homeostasis. Until then—please work safely—and don’t get cocky!