Traditionally, the focus of a fire department community risk assessment was the identification of fire hazards and planning an appropriate suppression response force to mitigate emergencies when they occur. Today, hazard or risk assessment goes well beyond the fire problem to medical and other emergencies. This all-hazards approach provides the opportunity to have a much bigger impact on life safety and property loss. At the same time, it makes the process of conducting a community risk assessment inherently more complex.

In my last article, I discussed the importance of using fire department operational data to demonstrate value to community members, elected officials and others. A risk assessment is an integral part of that process, because before you can demonstrate value, you must be able to match resources deployed to the need, and that starts with knowing your community’s risks and having a plan to manage them or mitigate risk events (incidents) when they occur.

Assessing community risks can be a complex process, but it helps to understand it by applying a simple three-part structure:

- Probability (likelihood) of an incident occurring

- Consequence (magnitude) of an incident on the community

- Impact of an incident on the department’s response system

Probability

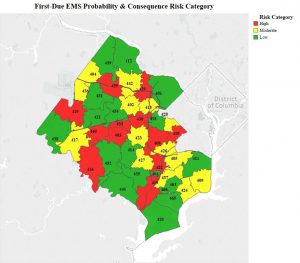

Probability is associated with the frequency of an incident type. For example, the probability of incidents occurring in a given census tract is related to the expected number of incidents in that census tract. Using Computer-Aided Dispatch (CAD) data and the demographic, social and physical characteristics of the census tracts where those incidents occurred, fire service leaders can conduct a statistical regression to help forecast the future number of incidents.

The predicted number of incidents is used to represent the probability of an incident occurring in each census track. Put simply: Incidents with high probability will occur more frequently. Once these predictions are made, the census tracts can be ranked (low, moderate, high).

Consequence

Consequence is the measure of the outcome of an incident type occurrence. To assess consequence, fire department leaders must first identify, categorize and prioritize community hazards. Hazards are the causes of danger and peril in the community. Risk quantifies the degree of potential danger the hazard presents.

In everyday conversation, we may use the term “hazards” to refer to events that can happen, such as a tornado or a fire. Within the context of community risk assessment for fire, however, a hazard may be a property or structure. Every property or structure carries inherent risks based on occupancy type and fire load. Occupancy risk is a sublevel of property risk and is established through an assessment of the relative risk to life and property resulting from a fire or emergency affecting a specific building/structure. Occupancy risk can also be established by applying generic occupancy classes (e.g., high-rise residential).

The consequences of an emergency incident result from a combination of the risk level of the hazard, the duration and nature of the event, and the response interventions. Consequences are divided into four categories:

- Civilian and firefighter injury or loss of life

- Property damage or loss

- Critical infrastructure damage or loss

- Environmental damage or loss

Impact

Impact is a measure that explains the effects of multiple concurrent incidents on the fire department. Impact describes a fire department’s ability to provide ongoing services to the remaining areas of a community considering frequent activity in known high-volume demand areas. Fire departments must have a plan in place to relocate response resources to ensure the best coverage possible considering temporary reduction in resource availability. These plans are traditionally called move-ups.

Any risk assessment methodology should include stable and known data from the U.S. Census, as well as dynamic information included in geospatially referenced parcel data.

Data Needed

It doesn’t take much thinking about the risk assessment process to realize it’s highly dependent on data. Any risk assessment methodology should include stable and known data from the U.S. Census, as well as dynamic information included in geospatially referenced parcel data. These elements provide a baseline from which to recognize an increase or decrease in the risk factors based on topographical inputs, socioeconomics, structure types, the presence of protection systems and ongoing risk-reduction efforts. While the risks are typically assessed using census tract perimeters, they may also be managed at the Service Demand Zone (fire station first-due) level or smaller geographic areas for deployment and administration purposes.

The following data elements (input factors) and information layers are necessary for effective community risk assessments:

- Computer-Aided Dispatch (CAD) Data (1 to 3 years preferred)

- Station first-due response zones (or fire box zones)

- Station first-due boundaries

- Building footprint and building type

- Parcel data (land/property value)

- Demographic data from the American Community Survey portion of the U.S. Census at the census block level preferred (gender, age, race, education, income/poverty, housing characteristics)

- Physical data (e.g., transportation network, utility lines, river and floodplains)

Note: These data elements have been compiled in the Community Assessment, Response Evaluation System (FireCARES) data system. Every U.S. fire department has a designated page with data in FireCARES. Visit https://i-psdi.org/firecares.html for more information.

The consequences of an emergency incident result from a combination of the risk level of the hazard, the duration and nature of the event, and the response interventions.

Matching Resources to Risk

Once the details of risks and hazards are known for a community, fire service leaders can plan and deploy adequate resources to either manage the known risks or mitigate the emergency when an adverse incident occurs (fire, hazardous materials incident, natural or man-made disaster, wildland fire or medical emergency).

For example, when considering resource deployment decisions, regardless of the size of a burning structure, firefighting crews must engage in four priorities:

- Life safety of occupants and firefighters

- Confinement and extinguishment of the fire

- Property conservation

- Reduction of adverse environmental impact

Each of these priorities encompasses several related tasks. The tasks can be conducted simultaneously (e.g., stretching a hose line to the fire, ventilation, search and rescue)—which is the most efficient manner—or consecutively (one after the other), which delays some tasks, thereby allowing risk escalation to occur.

In Summary

The process for assessing risk within the community requires a logical, systematic and consistent methodology that can be replicated over the entire community from year to year. And the lifeblood of that methodology is data—the unique mixture of demographics, socioeconomic factors, occupancy risk, known fire and emergency management zones, and the capacity and capability of the emergency resources provided.

Additional Resources

Following are several resources available to assist political decision-makers and fire service leaders in planning for adequate resource deployment in their community to ensure timely and coordinated firefighter intervention:

- NFPA Standard 1710: Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments specifies the number of on-duty fire suppression personnel sufficient to carry out the necessary firefighting task operations given expected firefighting conditions in various hazard-level occupancies.

- The Fire Protection Handbook identifies initial-attack response capabilities for low-, medium- and high-hazard occupancies.

- NFPA Standard 1600: Standard on Community, Emergency and Crisis Management establishes a common set of criteria for all-hazards disaster/emergency management and business continuity programs.

- United States Department of Labor – Occupational Safety and Health Administration – OSHA Regulation “2 in 2 out”– The “2 In/2 Out” policy is part of paragraph (g)(4) of OSHA’s revised respiratory protection standard, 29 CFR 1910.134. This paragraph applies to private-sector workers engaged in interior structural firefighting and to federal employees covered under Section 19 of the Occupational Safety and Health Act. States that have chosen to operate OSHA-approved occupational safety and health state plans are required to extend their jurisdiction to include employees of their state and local governments.

- NFPA 1500: Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety, Health and Wellness Program was developed to provide the framework for a safety and health program for a fire department or any type of organization providing similar services. This standard sets the minimum safety guidelines for personnel involved in rescue, fire suppression, emergency medical services, hazardous materials operations and special operations.

- Fire Service Deployment: Assessing Community Vulnerability is a white paper developed by the Metropolitan Fire Chiefs Urban Fire Forum to help fire service leaders understand how changes in levels of fire department resources affect emergency outcomes. Also see the second edition, which focuses on high-rise incidents.