Editor’s note: This article is part of a series. Click here for the previous article.

Gordon Graham here again. Thanks for your continued support by reading these articles, and for the kind emails about how you are making a difference by implementing some of the strategies from this series. I am always so happy to hear about public safety leaders putting additional control measures in place to prevent tragedies.

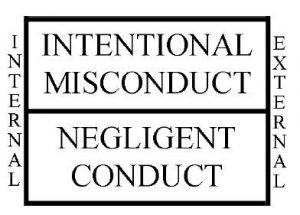

For the last two writings, I have focused on family five of the 10 Families of Risk—operational risk management. Once again (solely for purposes of continuity and absolutely not to fill up space), here is the chart I’m using to explore this issue:

We have addressed the issues on the right side of the chart, the external behaviors that sometimes cause police personnel grief. Now we will move to the left side of the chart—the internal behaviors that can end up in tragedy.

Let’s start with the top left corner: the internal intentional misconduct issues that plague police department operations around this great nation. If you have been to my live programs, you know I am a big fan of PoliceOne.com and FireRescue1.com and CorrectionsOne.com (all of which are now part of Lexipol!).

I look at these sites almost every day. Too often, I read about cops and firefighters and correctional officers doing bad things. I am fed up with misconduct in public safety. We all get painted with the same broad brush. When some bad cop does something bad 2,000 miles away from your police department, that behavior negatively impacts you and your personnel. Same thing for other public safety agencies.

Much of what you will see in the news is “internal intentional misconduct”—our own people doing bad things on purpose. Public safety personnel who lie, cheat, steal, perjure, beat, molest, assault, falsify, embezzle, murder and do otherwise bad things on purpose are a big deal to me—and I am confident they are to you also. We must address this issue. As I beat to death in earlier articles on organizational risk management, background checks—initial and ongoing—are a critical way to reduce police misconduct issues.

All too often I read cases involving assigned credit cards being used for personal benefit, including fancy watches or other types of jewelry, vacations, cash withdrawals and other forms of theft.

On a related note, we have an obligation to make it difficult to do bad things on purpose. If you look at public safety news headlines for the next five days, I guarantee you will find some intentional misconduct dealing with money: cops stealing from the DARE fund, volunteer firefighters embezzling funds raised to purchase new equipment, correctional officers cheating on overtime.

What can we do? Here is a thought. A simple requirement of two signatures on a check would do away with a lot of this behavior. I am always amazed that one person will have control of the checkbook with no audit process in place to see how the money is being spent. Regularly I read about misuse of credit cards, either city cards or cards in the name of a given charity. Who reviews the credit card statements, and how often are they reviewed? During some of my tenure with the California Highway Patrol, I had a state credit card—and I was very, very aware of the rigid audit process they had in place to make sure there was no misuse.

Yet all too often I read cases involving assigned credit cards being used for personal benefit, including fancy watches or other types of jewelry, vacations, cash withdrawals and other forms of theft. This is not limited to police departments; I am familiar with similar cases in fire departments and other city entities. If you get very bored some night and there is nothing to do and there are no reruns of the greatest TV show ever (that would be CHiPs), do a Google search for “financial scandal in Dixon Illinois” and you will be shocked. How could one person steal so many millions of dollars from the city and not be noticed?

I will bore you with this. Early on in my marriage my lovely bride (who, when I met her, was a bank teller) asked me, “Why do you never take a vacation?” I explained to her that on the patrol I could bank my vacation time up to a certain number of hours, and then at the end of my career I could “sell it back” to the state. It was a common practice to not use vacation time until you were maxed out.

Her response to this was, “You can’t do that in the bank. You have to take two weeks consecutive vacation every year, and if you come onto bank property during those two weeks, you get fired.” When I asked her what the logic was behind this rule, she patiently explained to me that if you were pulling some sort of financial scam, it would likely unwind in two weeks and you would be caught, fired and prosecuted. I stored this piece of information in my head way back then.

Decades later I learn about a narcotics lieutenant from a major police department who has successfully avoided going to the FBI National Academy for years. Finally the chief orders him to go in spite of his protestations. While he is gone for 11 weeks, a huge scandal is uncovered in the narc unit run by the lieutenant. His absence (against his wishes) allowed it to be discovered. There was a very sad ending to that story.

Of course, there are many other forms of internal intentional misconduct going on. But I’ll save that for our next visit together.