Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in The Chief’s Chronicle; New York State Association of Chiefs of Police. Reprinted with permission.

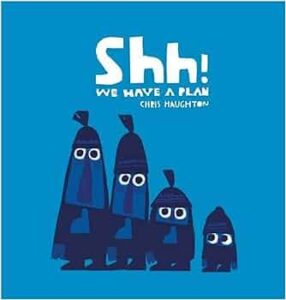

As a grandfather of three young children, I have been spending quality time reading children’s books with them. One such book, Shh! We Have a Plan, served as the inspiration for this article. In the book, four friends are creeping through a forest with nets, intent on capturing a bird. The smallest of the four sees a bird and calls out, “Hello birdie.” But the three larger friends are the planners, and they tell him, “Shh! We have a plan!” The three then try to sneak up on the bird: “Tiptoe slowly, now stop – ready one, ready two, ready three – GO!” Disaster strikes and the bird escapes.

In past articles and trainings, I have frequently discussed the importance of root cause analysis, which helps to identify why something (usually bad) happened. This is typically a post-incident exercise when it involves something that happened in your agency. But is there a way to push this into pre-incident training? I believe there is. It involves adaptive decision making, which is based on the fact that officers face a wide variety of situations that are unique and not suited to rigid “if this, then that” types of responses. Officers need to be able to identify the specifics of a situation and adapt accordingly.

Before developing this concept further, it may be helpful to apply Shh! and adaptive decision-making training to a couple of real-life examples. While the facts of these contemporary incidents are considerably different, the simple lesson of Shh! is applicable to both. But, as we will see, why an officer does not choose the simplest approach may be the most important lesson, as it can identify unforeseen problems.

The Stolen Vehicle & the Sleeping Subject

Officers identify a stolen car parked along a city street. There is a young man sound asleep in the driver seat. Cars are parked directly behind the stolen vehicle, but there is nothing parked in front of it. While the man sleeps in the car, officers from two departments gather nearby, attempting to come up with a plan to take the man in custody and secure the vehicle. Of primary concern is the possibility the driver will awake when approached by the officers, and this weighs heavily in their planning.

The officers had the right intent; they repeatedly noted that if the subject woke up and got startled, they should let him drive away so no one would get hurt.

Early in the discussion, an officer from one department offers several times to park his police SUV directly in front of the stolen car, effectively making it impossible for the driver to move in either direction. This option, however, is eliminated because a member of the primary agency says they are not allowed to block the path of a car. As a result, a more complex plan is created.

The rear passenger window is missing, replaced by plastic and tape. The plan is for one officer to cut through the plastic and unlock and open the rear passenger door, then use a baton to unlock the door on the other side of the car. Other officers will then open both doors and attempt to secure the man’s arms from both sides as he awakes, preventing him from putting the car in drive.

The officers had the right intent; they repeatedly noted that if the subject woke up and got startled, they should let him drive away so no one would get hurt. But that would require a split-second and accurate assessment by the officers. They would have to immediately assess whether the man was startled and would resist their attempts to secure him.

So how did this plan unfold? The doors were unlocked without incident, and it must have appeared to the officers that they had a chance to secure the driver’s arms because they entered the vehicle and struggled with him. But the plan quickly fell apart as they failed to physically control the driver. The driver put the car into gear and quickly drove down the road, knocking one officer on the driver’s side to the pavement. The officer who had entered through the passenger side was still in the rear seat. The officer repeatedly ordered the man to stop the car, but he continued to drive at a high speed. The officer then shot the driver several times, killing him.

The Pastor & The Peonies

A woman calls the police to report a suspicious man in the front lawn of a neighbor’s house. Officers arrive and find a Black man with a hose watering the bushes and flowers in the front of the house. One officer asks the man what he is doing there. The man quickly responds that he is watering his neighbors’ flowers, that his name is Pastor Michaels, he lives across the street, and he is taking care of the house while his neighbors are away.

Adaptive decision making in law enforcement is based on the fact that officers face a wide variety of situations that are unique and not suited to rigid “if this, then that” types of responses.

The officers’ subsequent request for the man’s identification is met with an angry refusal; he repeats that he is just watering the flowers. The officer tries to explain that someone called because he was suspicious but cannot explain who called or why Michaels is deemed suspicious.

Due to Michaels’ increasing agitation, the officers handcuff him and sit him on the front step. When he continues to verbally challenge the officers, they arrest him. While this unfolds, officers interview the caller. Once she sees the man up close, she immediately recognizes Michaels and confirms it’s likely he would be looking after the neighbor’s house. She then refuses to cooperate any further.

At this point, any suspicion that something is wrong should have immediately ended and Michaels should have been released. Instead, the three officers on the scene discuss charging him because he had refused to give his full name and identification. While Michaels is handcuffed and in a police car, his wife provides his ID to the officers. Despite this, he is arrested and charged with obstruction of governmental operations. Ten days after the arrest, the charges were dropped at the request of the chief of police. Michaels has filed a lawsuit against the department.

The Simplest Solutions Are Sometimes Hidden

As leaders in law enforcement, we must learn from these incidents and others like them. But this analysis and learning process cannot simply involve us casting judgment on the officers because we can see the incident as a whole and we know how it turned out. Instead, we must review such incidents with a focus on the processes implicated in the options available and chosen. Why did the officers choose to act the way they did, and how can we train our personnel to make better decisions in similar situations?

I chose these two incidents because, despite the factual contrast between the two, they both involve officers choosing paths that were more complex than perhaps they needed to be – and possibly for the wrong reasons. As we analyze each incident, imagine you are participating in adaptive decision making training exercise, such as a tabletop or roleplaying exercise. The goal is to determine how your officers “see” the incident. This can give valuable insight into not only how they make decisions, but also how they understand the applicable law and policy, which can identify additional unforeseen training needs.

Incident #1

For purposes of a training scenario, we would tell trainees the car is stolen, parked on a city street with cars behind but not in front, occupied by a sleeping man in the driver seat with a broken rear window covered with plastic. Here are your resources, have at it! The trainees should talk through the situation out loud, explaining not only what they would do but why. I will use my own thoughts for this exercise strictly as an example. You may think of other approaches.

What are the goals? Prevent the subject’s escape, take him into custody, and return the car to the owner. What are the priorities? Minimizing risk and, in order, keeping the public, the officers and the driver safe in the process. What are the perceived risks? The possibility of the driver waking up and trying to drive the vehicle away and/or otherwise resisting arrest.

What are our options? Three come to mind and all would require appropriate positioning of officers to keep them as safe as possible:

- Tapping on the window to wake the person up

- Blocking the car in with a police vehicle before tapping on the window

- Forcibly entering the car to restrain the subject before he can place the car in drive.

What is the relative complexity of each of these options? The first is the simplest but carries with it some risk if he tears off down the road and hits an innocent person. The second is more complex but eliminates the risk of the first option, and the third is both highly complex and high risk.

The officers chose the third option even though it was complex with multiple points of failure. It also required rapid interpretation of the suspect’s actions while the officers were under stress. Have they received training transferable to the situation? If not, would a simpler solution involve fewer points of failure, while attaining the goals of keeping the public, officers and suspects safe?

Now we come to the most critical point of this exercise. If the trainees choose the most complicated option, as in the incident, you will want them to verbalize why they did not take the apparently simplest option. And if the response is, “Our policy prevents us from blocking the path of a vehicle,” then the trainers need to evaluate this further. Is this a valid interpretation of policy? I have read many, many policies over the years and I have never seen a policy that would prevent blocking the path of a parked vehicle to reduce the risk to all individuals.

We become afraid to accept the simple answer because we could be wrong.

If it is not a proper interpretation of policy, you have just identified an additional training need. After all, if one officer interprets policy in this manner, others may as well. If the policy interpretation is accurate, then maybe you need to reevaluate the policy. As with training, policy cannot exist as one-size-fits-all in every situation.

Incident #2

The facts of this incident would be well-suited for a roleplay scenario instead of a tabletop exercise. For sake of brevity, I will analyze this incident based on how the officers responded. But the process is the same: What are the goals and priorities? The obvious and primary goal is to determine whether the man belongs at the residence.

In the video, one officer states that they are on a call and the man was suspicious so, therefore, the man had to give him his name because they had to have it for the call. But why is he suspicious – because they are on a call? Officers keep repeating “He’s a suspicious person” without articulating exactly why. One officer attempts to explain to the man that, “Any time the police come out and they say we want to identify you, you have to identify yourself because there is a reasonable suspicion” but his explanation becomes confusing and fails to provide any specific reason why Michaels was suspicious.

This would be the critical point of this exercise and is something that I have seen, unfortunately, repeated many times. The officers did not understand their legal limitations as they went into the incident. Unless officers have reasonable suspicion to believe a person is committing, has committed or is about to commit a crime, a person cannot be seized. They can refuse to provide ID and can outright refuse to speak with an officer. “I am on a call” without specific articulable facts to support reasonable suspicion is not enough.

“Yeah, but he could be covering for someone else who is inside burglarizing the house!” Yep, could be, but “could be” never has and never will be enough to support reasonable suspicion or probable cause. If you were just on patrol and drove by a man watering flowers, would you jump out and demand to know who he is or would you just wave as you drove by?

If you use this scenario for training, I hope that officers would want to interview the complainant to see exactly what they know or don’t know, especially when Michaels gives a plausible and reasonable explanation. It is important for officers to understand that being on a call does not change the law. Policy or procedure requiring “a name in the CAD” cannot change that.

Another training point is that the officers failed to realize that what makes sense to them may not make sense to everyone else. Video of the discussion between the three officers makes it clear they genuinely do not understand why Michaels would not give them his full name and ID – “He seems like a reasonable man.” They did not consider the perspective of a Black man who knows he is not doing anything wrong and who did willingly identify himself, up to a point. Those officers, and probably most people reading this article (assuming you made it this far), would immediately provide ID upon request of an officer because of our backgrounds. But many of the people we encounter have very different backgrounds and life experiences. Understanding this can go a long way to preventing unnecessary escalation of an incident.

The final point with this incident is that sometimes we become like those three people in the children’s book. “Shh, we have a plan!” We ignore the simplest solution – that the man did belong there – because, by the nature of the profession, we are trained to suspect and investigate everything. We become afraid to accept the simple answer because we could be wrong. Administrators and trainers need to make it clear that officers can only do what the law allows.

Embrace the Training Challenge

While I focused on two specific incidents, this article is just a brief foray into a much broader topic and training effort. The benefits of adaptive decision making in law enforcement training are not limited to developing individual officers. When trainers develop scenarios, they should not be assuming they can provide conclusive answers to the issues presented. They should instead be open to learning something they did not expect or foresee, which can lead to identifying additional training needs and or policy revisions.

And if you are wondering where you can find scenarios, just follow the news. Look at police-related videos online. Use viral incidents from around the country as the basis for scenarios. You do not need to reinvent the wheel. What you may need to reinvent, however, is how you prepare officers to think adaptively to solve problems in a manner that presents the least risk of harm for everyone involved.

References and Notes

- Haughton C. (2015). Shh! We Have a Plan. First United States board book edition. Somerville, Massachusetts, Candlewick Press.

- I have modified this name and, for both incidents, withheld information that would make the agencies involved readily identifiable. There is no reason to unnecessarily subject the departments and officers to any more exposure than they have already received. I spent a considerable amount of time watching video and otherwise researching these incidents. As a result of this research, it is my belief that the officers involved in both genuinely believed they were doing the right thing. The purpose of this article is to prevent other officers from making the same mistakes.

- For a further discussion of how it can be important to understand how officers “see” an incident, view the Lexipol webinar Why Do Bad Things Keep Happening? Insight vs. Hindsight.