Law enforcement involves specialized and often challenging training, intense physical and mental alertness, and high levels of responsibility. The job itself can become the central and defining aspect of a law enforcement professional’s life.

While allowing the job to take over our identity can at first be fulfilling and even exciting, for many law enforcement officers, it may eventually cause negative repercussions. Chronic anger, depression, social isolation, shiftwork, poor diet, and lack of recreation and exercise take their toll. Police suicides have outnumbered line-of-duty deaths for three straight years, according to statistics compiled by Blue H.E.L.P. and Officer Down Memorial Page.

Sadly, as a profession we do little to prepare our officers for the emotional challenges of the job. Physical safety is a huge component of law enforcement training, but we don’t place the same emphasis on emotional awareness and training.

Many law enforcement leaders are beginning to advocate for greater focus on mental and emotional health. This is a welcome change. One of the best books on the subject was first published in 2002: Emotional Survival for Law Enforcement by Kevin M. Gilmartin, Ph.D.

Recently I revisited this classic text and found it more relevant than ever. Dr. Gilmartin, a clinical psychologist with 20-plus years as a deputy sheriff, is uniquely qualified to delve into the emotional and physical tolls our stressful occupation takes on us, our families and our friends. Dr. Gilmartin gets it. He contends that the transition from idealistic rookie to cynical veteran often includes withdrawing from friendships and activities outside of law enforcement, a breakdown of marital relationships and even disconnection from children.

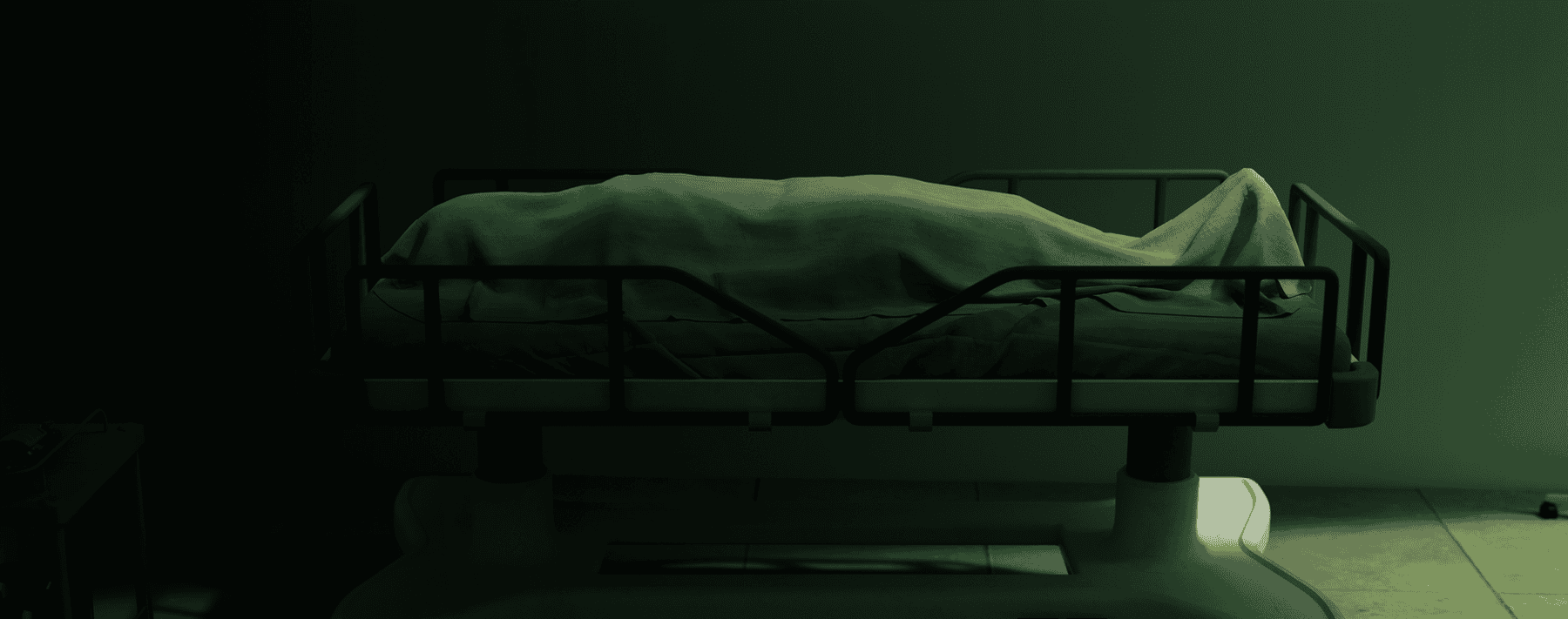

According to Dr. Gilmartin, the long-term impact of a law enforcement career can include cynicism, new thinking patterns and damage to personal relationships. He also writes about hypervigilance—viewing the world from a threat-based perspective—and its impact on the human body. More importantly, he tells us the hypervigilant, active, alert, energetic on-duty officer can become a tired, detached, isolated and apathetic—or angry—couch potato when off duty. Gilmartin calls these two opposite states the “hypervigilance biological rollercoaster.”

The hypervigilant, active, alert, energetic on-duty officer can become a tired, detached, isolated and apathetic—or angry—couch potato when off duty.

The hypervigilance biological rollercoaster that causes the “high” at work may swing to a low at home, causing the officer to desire social isolation. This can often include an unwillingness to engage in conversation or activities that are not police-related, as well as reduced interaction with nonpolice friends and acquaintances. Other traits may involve procrastination in decision-making not related to work, infidelity, a lack of involvement in children’s needs and activities, and loss of interest in hobbies or recreational activities the law enforcement professional once enjoyed.

Not only does Emotional Survival walk the reader through the changes a person experiences during a career in law enforcement, it also details how to become an emotional survivor. Four of the key points are:

- Time management and planning are essential to taking control of one’s personal life. Don’t plan to go fishing “when things slow down.” Plan to go fishing on the opening day of trout season, and then do it. Plan to watch your daughter’s play—and do it. Sometimes the job or court will get in the way, but if you don’t plan to do something, it will probably never happen.

- Survivors practice physical fitness. Just 30 to 40 minutes of aerobic activity, four to five times a week, can rebalance the biological rollercoaster.

- Survivors control their financial wellbeing. Money troubles are a huge source of stress and marital discord. Stress-related spending, followed by racking up overtime or taking an outside job to pay for expensive pickups, boats and other items, may lead to more anger and frustration.

- Survivors embrace roles beyond being cops. They are parents and spouses. They are also (or at least they “usta be”) golfers, softball coaches, woodworkers and artists. Survivors have interests and priorities other than police work. Survivor families choose to put family events and other activities above department events. Again, sometimes work or court will intrude, but survivors do what they can to make time for other things.

If you are associated with law enforcement, you need to read this book. Partners of men and women involved in police work or corrections should also make time to read Emotional Survival for Law Enforcement. Although this little paperback book is only 142 pages, it is rich with information and, more importantly, insight and practical problem-solving. Partners of law enforcement professionals will gain insight into the changes their partner may experience. Most men and women in law enforcement will, if they are honest with themselves, recognize their own behaviors, reactions, attitudes or conduct somewhere in the pages. I did.