January 2022 is one for fire history books. In the span of a few weeks, 12 people died in a Philadelphia fire and 17 more died in a Bronx fire, along with three firefighters in Baltimore. In all, 327 civilians and 13 firefighters died. And the tragedy wasn’t limited to the northeast; Michigan reported a 144% increase in fire deaths during the same time.

Sadly, the reasons for much of the death and destruction have been researched, analyzed and discussed long before now.

During Fire Prevention Week, we conduct the annual push to inform our kids about the dangers of “playing with matches.” But is that necessarily where we should put our limited resources? Are school-age kids an “at-risk” group? Better yet, let’s refine that statement: Are school-age kids in your community an “at-risk” group likely to be injured or die in a residential fire? We should refine the question one more time: What demographic groups in our communities are at the most risk for injury or death due to a residential fire?

Nationwide data suggests that our communities would be better served if we refocused our fire prevention efforts on disadvantaged communities, senior citizens and parents of preschool-age children. That data also shows living in poverty increases the risk for these groups. Moreover, the specter of racism in housing policies cannot be ignored.

The fires in Philadelphia (in a low-rise duplex row home) and the Bronx (in a high-rise apartment building) occurred in subsidized or public housing. The fatal Baltimore fire occurred in an abandoned row house attached to an occupied home located in a disadvantaged neighborhood.

No one in government should be surprised that these fires occurred. The only thing that should be surprising is the number of casualties. Fires like these three occur every day in every corner of the country. They do not garner national attention because they are small events and only the local news media will report on them.

Still, each fire resulting in injury or death has commonalities that should not be ignored. Studies going back 50 years have examined the factors contributing to fire-related injuries and death. Contemporary studies identify the same factors identified in the 1970s: poverty, race, age, housing and zoning.

While these factors relate to deep-rooted societal issues, fire service leaders should not feel helpless. There is much we can do to better understand who’s at risk in our community and take steps to mitigate the risk.

Identify Vulnerable Groups

Much of the work of understanding who’s at risk in your community has already been done for you. Age, poverty, housing, race and residents for whom English is a second language are the leading indicators of vulnerable groups. Your task is to identify where these folks live, go to school or work.

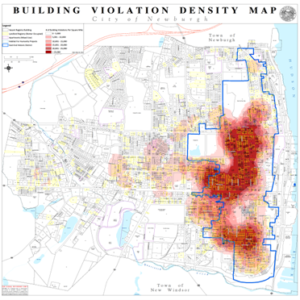

Publicly available census data is key here. Everyone knows where the poor side of town is located. But what do you really know about your community or its neighborhoods? By combining census data with data from the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS), building department, police calls, EMS calls, and if possible data from the health department and social services, a picture of your community’s vulnerable populations will come into focus.

Moreover, if your community has GIS services available, the data can be transformed from numbers on a spreadsheet into a picture that tells a story. This map was an early effort (2010) to translate reams of spreadsheet data into something people could easily understand.

Courtesy City of Newburgh

Identifying vulnerable groups in your community also requires an understanding of the factors that make them vulnerable to death and injury by fire. Specifically, let’s take a look at two of these factors, poverty and housing.

Poverty as a Risk Factor

A recent article in the Economist boldly pointed a finger and stated the obvious: that poverty was the real cause underlying the deadly fires in Philadelphia and the Bronx. Members of the fire service have long known this. Yet both the fire service and its political governing bodies have only nibbled at the edges of the fire problem affecting the poor.

Numerous studies and reports implicate poverty as a major factor in causing deaths and injuries by fire. The connection between poverty and fire has been documented since the 1970s. A 1978 report studied fires by census tract in five large cities and found “strong associations between fire rates and several social indices, including poverty, family stability, crowdedness, and the percentage of owner-occupied homes.”

Later studies in both Philadelphia and Dallas found significantly higher rates of fire in low-income census tracts when compared to higher-income tracts. The same Philadelphia study noted above that fire injuries occur most frequently in older housing, in census tracts with a high percentage of vacant buildings, and in those same tracts where English is not the first language. A 1983 report published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that fatal house fires occur most frequently in census tracts where the rental values are low. Moreover, fires caused by electrical devices occurred nine times more often in the lowest value census tract versus the highest value census tract.

The connection between poverty and fire has been documented since the 1970s.

The United States Fire Administration released a report in 1997 examining socioeconomic factors and the incidence of fire. An interesting finding was that comparisons between cities are not useful. On the other hand, comparisons between census tracts in the same city are better for examining fire experience. The factors that explain the difference in fire incidence between census tracts are parental presence, poverty and under-education (meaning the 8th grade or less.)

In urban communities, poverty can be synonymous with race. A report published in 1984 compared the death rates due to injury between Black Americans and white Americans. This study found that Black residents have a higher death rate than white residents in residential fires. Contributing factors include lack of smoke detectors, poor housing, and inappropriate use of heating devices. Both the Philadelphia and Bronx fires lacked functioning smoke detectors, issues with heating, and poor housing maintenance.

Housing Conditions as a Risk Factor

Housing conditions have always been an issue when discussing groups particularly vulnerable to death and injury by fire. In the early 1900s, these discusions took on greater urgency as city planners confronted the question of what to do about poverty and overcrowding. The Regional Planning Association of New York and its Environs (RPA) released its first Master Plan in 1929 noting “Some of the poorest people live in conveniently located slums on high-priced land.”

Progressive policy’s solution was to rid cities of their industrial base, level functional neighborhoods, and crowd families into housing that the cities cannot maintain. Money pouring into cities from New Deal programs was used to clear slums and construct affordable housing in less expensive areas. By 1938, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia estimated the city had torn down over 9,000 buildings. In Philadelphia, 8,328 buildings were torn down under New Deal programs. Many reformers believed that by simply getting rid of the slums, poverty would miraculously disappear. This method proved disastrous when implemented as public policy.

If your community is not engaging in a Community Risk Reduction (CRR) program, advocate for the need to begin one.

Following the New Deal, redlining—the isolation of impoverished communities that have been deemed unworthy of additional investment—became common. (The term originated with the practice of drawing a red line on a map around the targeted area.) Banks refuse to lend money to maintain privately held properties, insurance companies will not insure those properties, and the real estate industry is looking to clear land to have a fresh start. Today the practice is called planned shrinkage.

Planned shrinkage came into vogue during the financial crises cities faced in the 1970s. In short, planned shrinkage strangles neighborhoods by reducing and withdrawing essential city services such as police, fire, sanitation and public transportation. People move out, making room for new development to move in. During the Great Recession, planned shrinkage once again moved to the forefront in many of America’s cities.

Planned shrinkage is an accelerated version of Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s theory of benign neglect. The broad definition of benign neglect is a policy of ignoring an undesirable situation that one is responsible for dealing with. In historical urban policy, it means disinvestment in poor communities, which falls primarily along racial and class lines.

Vacant Properties as a Risk Factor

A 2011 study conducted by Johns Hopkins School of Public Health researchers examined the relationship between vacant buildings and increased fire risk at both the census tract and individual property level. This study echoes the 2006 study in Philadelphia that found census tracts with a high number of vacant buildings will have an increased number of fire-related injuries.

There is a mantra, or one could call it dogma, that a building is not worth a firefighter’s life. Yet the problem with the statement is that it is too simple. And the problem with “too simple” is that it can become the only acceptable choice. Firefighting is not always simple.

Nationwide data suggests that our communities would be better served if we refocused our fire prevention efforts on disadvantaged communities, senior citizens and parents of preschool-age children.

The Baltimore fire is one example. The fire building was attached to at least one occupied structure. In many poor neighborhoods in America’s oldest cities, this is a common sight: blocks of similar attached buildings, with one or more abandoned buildings punctuating the row. Remember our core mission is protecting lives and property. The choice was made to defend the occupied buildings by committing to an interior attack. This is a valid choice made on arrival.

Consider the seasons. Simply because the owner abandoned the property does not mean it’s unoccupied. The unhoused population, seeking a spot to get out of the weather, often chooses abandoned properties over shelters. These folks start fires to keep get warm, not to destroy the property. This use of abandoned properties is so common that many unhoused folks call them “abandonminiums.”

If this fire occurred later in the day, the cause could have been children playing in the building instead of someone trying to get out of the cold. The fire was started by a person because most abandoned buildings have had their electricity and gas shut off.

Why wasn’t it secured, you ask? Maybe it was secured and then later forced open by kids, scrappers or the unhoused. But many cities continue to have serious problems with abandoned properties. Just keeping track of them is difficult; keeping them secured is next to impossible. Baltimore has 15,000 vacant or abandoned buildings. The Census Bureau reports more than 6,000,000 vacant housing units in the United States (listed as “other vacant”).

How the housing market will fair post-pandemic remains conjecture. The policies put into place to protect tenants may force small rental property owners to walk away, much like homeowners did during the mortgage foreclosure wave of the Great Recession. If this happens, the fire service will be dealing with another wave of abandoned properties and the problems that go with them.

What Can Fire Service Leaders Do?

It can be daunting to confront the deep-rooted issues of poverty, race and housing policy. But fire service leaders don’t have to solve these problems to have an impact. There is a lot we can do that is well within our sphere of expertise and control. Following are just a few ideas:

- Develop a Community Risk Reduction plan. If your community is not engaging in a Community Risk Reduction (CRR) program, advocate for the need to begin one. The focus of CRR is lower the risk to your communities and residents by focusing on the five Es: Education, Engineering, Enforcement, Economic Incentives, and Emergency Response. The National Fire Academy provides online self-study to get you started. Additionally, the NFPA has developed a standard for developing a CRR plan.

- Advocate for residential sprinklers. Fire service leaders should work tirelessly to have residential sprinklers installed in public and subsidized housing. A report written by Division Chief Charles Kirby in 1970, early in the “War Years,” contained this line in the summary and conclusion: “The city should develop a realistic program for sprinkler installation. . .for multiple dwellings.” More than 50 years later, Philadelphia Fire Commissioner Adam Thiel commented on the lack of sprinklers, noting that sprinklers are required in newly constructed row houses, but that retrofitting the 19th-century row homes would “be a tall order.”

- Engage in targeted intervention. Research has shown that targeted interventions such as a smoke detector installation program are effective at reducing the number of fires along with fire injuries and deaths. Targeted code enforcement efforts can make a difference when resources are slim. Reach out to groups located within the identified census tracts. Their knowledge can provide valuable assistance and information to help shape the program.

- Push for comprehensive vacant building legislation. Simply marking the building with a square and an “X” is not sufficient. Advocate for legislation that includes some form of registry and method to get that information to fire companies and keep it updated.

- Embrace technology. Along with spreadsheets and GIS data, artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming more accessible. Atlanta, New Orleans, New York, Pittsburgh and Rochester, N.Y., have had success harnessing AI using predictive analysis to identify data patterns not discernable with simple spreadsheets.

Conclusion

The fire service must play the hand it was dealt. Bad public policy, financial crashes, the convergence of the F.I.R.E (Financial, Insurance and Real Estate) industries, and bureaucrats who want to apply simple solutions to complex problems all come back to the fire department after the developers and bureaucrats have moved on.

You may be asking yourself, why did he write so much about this? It doesn’t affect my day-to-day job of responding to fire, rescue and emergency medical incidents. But that’s not exactly true. All these policy decisions made over the past 100 years contribute to conditions that exist today. The fire department does not operate in a vacuum. Decisions affecting your job do not only arise from the city council, but also from the planning and zoning boards. The fire department should have a seat at discussions involving issues that will become the fire department’s problem at 2:00 a.m. on a holiday weekend.

Consider this example from New York in the 1970s: “The NYC Planning Commission informed the Fire Department that parts of the Rockaway section of Queens were to undergo urban renewal and that ‘fewer fire units would be needed’ because the new construction would be fire-resistive. Not included was the fact that only a couple of blocks of the old housing would be torn down. After the fire department closed a fire company, large portions of Rockaway were burned down, thereby clearing additional land for redevelopment without the city incurring the costs of legal urban renewal.”

George Santayana famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” As fire service leaders, we have a responsibility to intervene to make things safer in our communities—and to ensure our perspective is heard in policy and planning discussions.

References

- (2022) Deadly blazes reflect America’s failure to adequately house its poor. The Economist. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.economist.com/united-states/2022/01/13/deadly-blazes-reflect-americas-failure-to-adequately-house-its-poor.

- Adams C. (2022) Fire tragedies in Philadelphia and the Bronx underscore systemic racism in urban planning.” NBC News. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/tenants-have-no-choice-racism-in-urban-planning-fuels-high-rate-of-black-fire-deaths/ar-AASIsuK.

- Bishai D, Sunmin L. (2010) Heightened Risk of Fire Deaths among Older African Americans and Native Americans. Public Health Reports. 125(3):406–13. Accessed 3/5/22 from https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491012500309.

- Brown H, Tracy T. (2022) FDNY: Constant use of multiple space heaters sparked fire that killed 17. New York Daily News. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.firerescue1.com/fatal-fires/articles/fdny-constant-use-of-multiple-space-heaters-sparked-fire-that-killed-17-2TyCuAtqd1jx9dG0.

- Cebul B. (2020) Tearing Down Black America. Boston Review. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://bostonreview.net/articles/brent-cebul-tearing-down-black-america/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1988) Differences in Death Rates Due to Injury Among Blacks and Whites, 1984. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001759.htm.

- Fahy R, Maheshwari R (2021) Poverty and the Risk of Fire. National Fire Protection Association. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.nfpa.org/~/media/Files/News and Research/Fire statistics and reports/US Fire Problem/ospoverty.pdf.

- Flood J. (2010) The Fires: How a Computer Formula, Bid Ideas, and the Best of Intentions Burned Down New York City – and Determine the Future of Cities. Riverhead Books.

- Gilbert S, Butry D. (2018) Identifying vulnerable populations to death and injuries from residential fires. Injury Prevention. 24(5). Accessed 3/5/22 via https://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/24/5/358.

- Istre G, McCoy M, Osborn L et al. (2001) Deaths and Injuries from House Fires. New England Journal of Medicine. 344:1911–1916. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM200106213442506.

- Jennings C. (1996) Urban Residential Fires: An Empirical Analysis of Building Stock and Socioeconomic Characteristics for Memphis, Tennessee. Cornell University.

- Mallonee S, Istre GR, Rosenberg M et al. (1996) Surveillance and prevention of residential-fire injuries. New England Journal of Medicine. 335(1):27–31. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8637539/.

- Messerschimidt B. (2022) Who Dies in Fatal Home Fires? National Fire Protection Association. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Publications-and-media/Blogs-Landing-Page/NFPA-Today/Blog-Posts/2022/01/12/Who-dies-in-fatal-home-fires.

- Mierley M, Baker S. (1983) Fatal House Fires in an Urban Population. JAMA. 249(11):1466–68. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1983.03330350042024.

- Orso A. (2022) Philly Fire Commish: ‘Root Cause’ of Horrific Fire Is Lack of Safe, Affordable Housing. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.fireengineering.com/leadership/philly-fire-commish-fairmount-fire/?fbclid=IwAR2selI406EKHB9qwshJfMTR-1DaYhXU33RJLfnAd2E-B7jFlDB4FDwnVNA.

- Schachterle S, Bishai D, Shields W et al. (2012) Proximity to vacant buildings is associated with increased fire risk in Baltimore, Maryland, homes. Injury Prevention. 18(2):98–102. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040022.

- Shai D. (2006) Income, Housing, and Fire Injuries: A Census Tract Analysis. Public Health Reports. 121(2):149–54. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490612100208.

- Shaw K, Mccormick M, Ruddy R et al. (1988) Correlates of Reported Smoke Detector Usage in an Inner-City Population: Participants in a Smoke Detector Give-Away Program. American Journal of Public Health. 78(6):5. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3369594/.

- Surico J. (2022). The Big Plans That Built New York City. Bloomberg. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-02-02/how-new-york-s-master-planners-shaped-a-metropolis.

- U.S. Fire Administration. (1997) Socioeconomic Factors and the Incidence of Fire. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/statistics/socio.pdf.

- United States Fire Administration (n.d.) Community Risk Reduction. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.usfa.fema.gov/prevention/crr.html.

- Wallace D, Wallace R. (2001) A Plague on Your Houses: How New York Was Burned Down and National Public Health Crumbled. Accessed 3/5/22 from https://books.google.com/books/about/A_Plague_on_Your_Houses.html?id=WqxzT1nM12wC.

- Wallace D, Wallace R. (2017) Benign Neglect and Planned Shrinkage. Verso Books. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3145-benign-neglect-and-planned-shrinkage.

- Wallace D, Wallace R. (2018) Death and Destruction by Algorithm: A Mask for Human Rights Abuses. New York State Psychiatric Institute. Accessed 3/5/22 via https://christianregenhardcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/wallace-death-and-destruction-by-algorithm-04282018.pdf.

- Wallace R. (1977) Studies on the Collapse of Fire Service in New York City 1972-1976: The Impact of Pseudoscience in Public Policy. University Press of America.