Hyman v. Lewis, 2022 WL 682543 (6th Cir. 2022)

In the course of a traffic stop, officers discovered a felony warrant for Deandre Lipford. They arrested him and booked him into the Detroit Detention Center. As part of the intake process, detention officers searched Lipford twice and did not find any contraband. Lipford told jail health staff he was not under the influence of drugs and had no drugs in his possession.

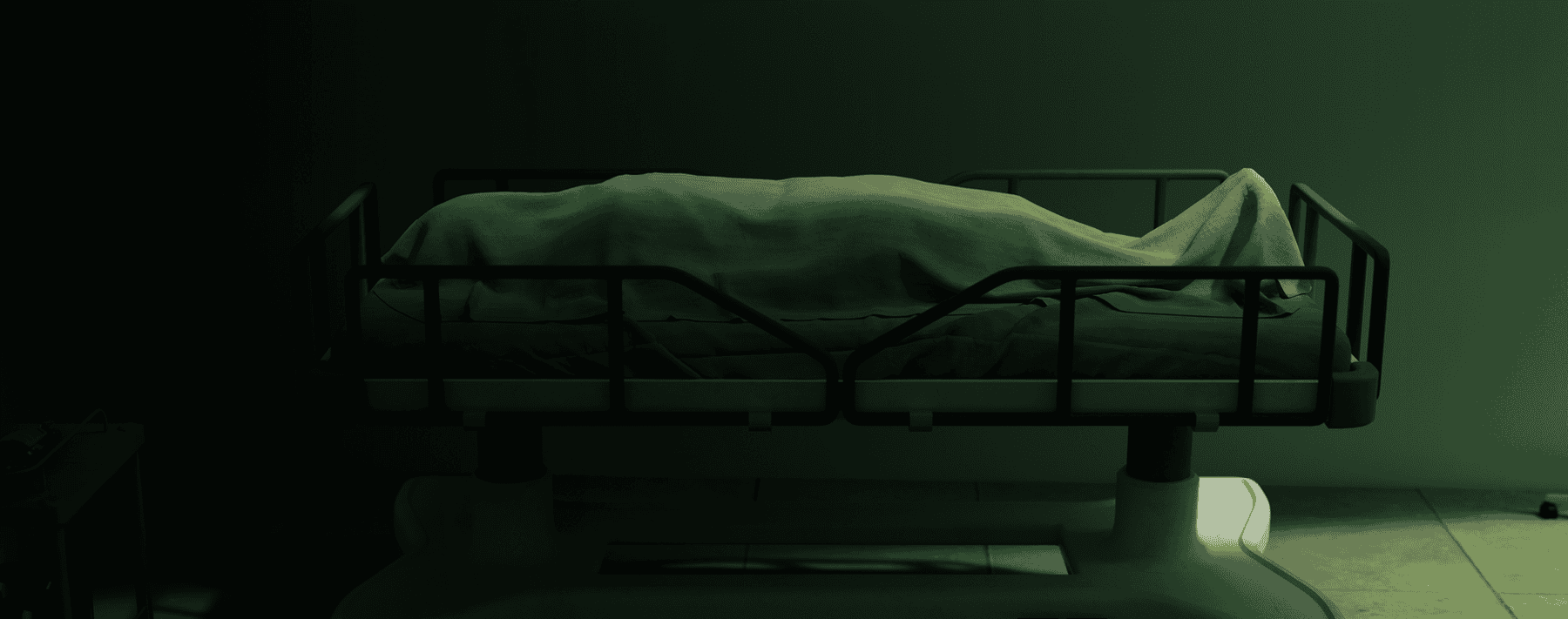

At 2148, officers placed Lipford in a glass-walled room used to hold multiple detainees awaiting video arraignment. Lipford laid down, sat back up and nodded off. He slid to the floor at 2302 and laid there motionless until 0250 when a jail worker found him found unresponsive. Jail staff provided emergency aid to no avail. Lipford was pronounced dead at 0350. Hospital staff found cocaine, heroin and fentanyl concealed in paper tucked into the cleft of Lipford’s buttocks. The medical examiner ruled the death an accidental overdose.

The jail’s operating procedures require officers to conduct rounds every 30 minutes and “physically open the cell doors and ensure that those detainees that are assigned to the cell are actually there,” to “check to make sure that every detainee is living and breathing.” Officer Clyde Lewis was assigned to make the half-hour checks. Though he ostensibly made his rounds that night, he did not physically enter the video arraignment room as required by policy. Instead, he looked through the glass surrounding the room without entering or speaking with the detainees. Jail staff had a practice of simply conducting a visual inspection and not waking up inmates. The detainees would become agitated at officers waking them up.

Lipford’s estate sued. The appellate court affirmed the trial court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of Lewis. Beginning with the principle that pretrial detainees have a right to adequate medical care under the 14th Amendment, the court observed the plaintiff must show the officer acted with deliberate indifference to Lipford’s serious medical needs. The appellate court defined the applicable test as showing “(1) that the detainee had an objectively serious medical need; and (2) that the defendant officer’s action (or lack of action) was intentional (not accidental) and that she recklessly failed to act reasonably to mitigate the risk the serious medical need posed to the detainee, even though a reasonable official in the officer’s position would have known” of that risk.

Though the court upheld the grant of summary judgment and dismissal of the case for Lewis, corrections officers should not take too much comfort in the court’s rejection of the claim that a policy violation could lead to liability.

Applying the test, Lipford’s estate needed to show that a reasonable officer in Lewis’ position would have known Lipford was potentially concealing drugs, subjecting himself to an excessive risk of harm and that Lewis ignoring this risk was objectively reckless. The court held the plaintiff failed to meet that burden. Two searches failed to find any drugs, Lipford denied being under the influence of drugs or holding any drugs, and Lipford never showed any signs of an overdose. None of the other three persons in the video arraignment room signaled any concern that there might be something wrong with Lipford; he simply nodded off and slipped into unconsciousness. There was no evidence that a reasonable officer in Lewis’ position would have been aware of Lipford’s medical needs (to be protected from the effects of his hidden dangerous drugs).

Lipford’s estate argued Lewis was objectively reckless by ignoring the risk to Lipford. The plaintiff claimed Lewis “intentionally” did not check on Lipford every 30 minutes as required by internal policy. The court acknowledged Lewis’ actions “might have been imprudent,” but held that his actions did not show he was acting “in the face of an unjustifiably high risk” that any reasonable officer would have known. Lewis had no reason to believe Lipford had concealed dangerous drugs in his body. The court noted, “Lewis no doubt violated the jail’s operating procedures. But failure to follow internal policies, without more, does not equal deliberate indifference.”

Though the court upheld the grant of summary judgment and dismissal of the case for Lewis, corrections officers should not take too much comfort in the court’s rejection of the claim that a policy violation could lead to liability. In this case, Lewis escaped liability, in part, due to the lack of evidence that he should have known Lipford was concealing drugs. Right or wrong, many judges will still permit jail operations policies as evidence to show a standard of care. There’s a sound reason behind 30-minute checks and a solid policy requiring them. Adhering to that policy is the best practice.